-1.png?width=534&name=image%20(1)-1.png)

Since January, Advanced Energy Economy has been tracking hundreds of pieces of energy-related legislation filed in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the United States Congress. With some sessions already over and some just beginning, a number of trends have begun to emerge. Of course, just getting filed does not mean a bill will become law, or even that it stands much of a chance at all. But the patterns that arise in our survey of filed bills, which is by no means exhaustive, say a lot about what’s on lawmakers’ minds. And of course, some bills are already on the move. In what follows, bills with an asterisk have passed one house of its legislature as of May 25; two asterisks means that the bill has passed both houses (click through to see if it has been signed into law). We’ll be back this fall to catch up on what legislation has made it all the way to gubernatorial desks. For now, here is a look at our top 10 energy issues generating legislative activity across the country.

The trends that emerge from 2021 legislative filings tell us a few things about the state of energy policy in the United States. First, there is a growing divide between states and lawmakers looking to accelerate the transition to cleaner energy, and those looking to hang onto the status quo for a while longer. Among those gunning for rapid transformation, there is a new sector-specific focus, including and especially transportation. There is also an intensifying focus on how to use new growth in the energy industry to support those who have been previously harmed by environmental or other systemic injustices, and those for whom a career pivot is increasingly inevitable. Ultimately, states that can harness the shift that is underway and leverage a new federal focus on clean energy jobs and infrastructure will reap the most benefits. The first step to this, of course, is the introduction of bills.

Note: most links in this post reference bill filings and other documents in AEE's software platform, PowerSuite. Click here and sign up for a free trial.

1. Environmental Justice and Equity Take Center Stage

Environmental justice (EJ) is appearing more than ever before in state legislatures. Each state has its own term – including “environmental justice community or population,” “disadvantaged community,” “historically underserved community,” and “overburdened and underserved community” – and qualifying criteria, but the intent is generally similar. More and more state legislators are recognizing that a whole lot more needs to be done to address historical inequities and that they have the power to be a part of the solution. The following non-comprehensive survey demonstrates the breadth of issues across which environmental justice is now appearing, and how state legislators have, to date, been thinking about potential remedies and proactive efforts.

EJ-specific bills have been introduced in at least 17 states and the U.S. Congress. Many address facility siting, ensuring that EJ communities participate in public processes and that utilities and Public Service Commissions consider health and environmental impacts when approving projects. These include Massachusetts S2186, New York S01031*, Georgia HB339, Virginia HB2221*, Colorado HB1266*, and Maryland SB121*. Oregon’s HB2488 proposes to reconsider statewide land use planning goals to support EJ communities. Notably, a few siting-related bills (Massachusetts H3336, Rhode Island S0105, Virginia HB2074*, Georgia HB431, Texas SB1294 and HB1191, Connecticut HB06551, and Minnesota SF1745, HF2170, and HF2334) explicitly note the need to identify cumulative impacts, rather than the impacts of each energy-related plan or policy in isolation. A resolution in Oregon, SCR17*, establishes a framework and principles for the application of EJ.

Other bills that focus predominantly on EJ include Illinois HB3090, Texas HB714, Vermont S0148, and Arizona SB1563 to create EJ Advisory Councils, and Nevada ACR3 to ask for an Interim Committee to study EJ. Pennsylvania SB189 creates an Office of Environmental Justice, an EJ Advisory Board, an EJ Task Force, and Regional EJ Committees, and Washington SB5141** implements the recommendations of the Environmental Justice Task Force. Oregon SB286 strengthens environmental vulnerability assessments, Maryland HB1207** reforms the Commission on Environmental Justice and Sustainable Communities, Illinois HB2647 targets clean energy workforce development towards economically disadvantaged communities, and Massachusetts S2168 requires that all incentive programs for solar, storage, electric vehicles, and renewable heating reserve dollars for low-income and EJ populations, S2138 dedicates at least 70% of Transportation Climate Initiative revenue to benefit EJ communities, and S2142 focuses on net metering reform to expand solar access to EJ households. Hawaii SB1277 and U.S. Congress SB101 and HB516 focus on the EJ mapping tools and data.

Another common approach has been to embed EJ provisions within other bills. Two omnibus energy bills in Illinois, HB0804 and SB1718, create Equity and Empowerment in Clean Energy Boards and workforce programs targeted to Black, Indigenous, and People of Color communities. Oregon HB2021 accelerates emissions reduction targets, but includes a Community Benefits and Impacts Advisory Group with EJ participants to biennially assess the impacts of clean energy plans on various communities. Maryland SB414*, Rhode Island S0078** and H5445**, Massachusetts S2229, New Hampshire SB115, Florida H0283, and VA HB1937 are also omnibus energy bills that require EJ considerations, prioritization, or investment.

Another major climate bill, Colorado SB200, implements the state’s greenhouse gas reduction goals and creates an EJ Ombudsperson and Advisory Board. Massachusetts S2131 requires a Climate Policy Commission to host mandatory public meetings in EJ communities. Oregon HB3180 requires the Public Utilities Commission to consider EJ and social equity when reviewing utility clean energy implementation plans.

Some sector-specific bills also include nods towards equity. In energy efficiency and building electrification, Nevada SB382 mandates more spending that targets low-income and historically underserved communities, New York S03126* directs energy efficiency job training, hiring and funding toward priority populations and EJ communities, and future-of-heat bills in Massachusetts prioritize funding and financing for homes within EJ populations (H3365 and S2148). Other Massachusetts bills seek to focus the benefits of transportation electrification on EJ populations, either with targeted vehicle incentive programs and outreach, the intentional siting of charging infrastructure, or by prioritizing the electrification of transit vehicles that travel through EJ communities (H3347, H3255, and S2127), and Rhode Island S0872 directs at least 35% of proceeds from the Transportation Climate Initiative auction of allowances to benefit overburdened and underserved communities. Nevada SB448 directs 40% of a $100 million investment in transportation electrification into historically underserved communities. North Carolina S509 focuses on resiliency infrastructure with a priority for projects that benefit EJ communities.

2. In State Fleets, Electric Motors Get Phased In, Internal Combustion Engines Get Phased Out

As states set goals to electrify and decarbonize their transportation sectors, they are running up against a hard truth – consumer choices about personal transportation vehicles are not entirely within their control. But states do have direct authority over the procurement of public vehicles. With that in mind, many are considering bills to set phase-in schedules for state, county, municipality, and transit agency light-, medium-, and heavy-duty zero-emission vehicles into their fleets.

For example, Arizona SB1009 requires 100% of state fleet vehicle purchase to be electric beginning in model year 2022. Beginning in Fiscal Year 2023, Maryland HB592* disallows the purchase or lease of non zero-emission vehicles for state fleets, and HB334 requires the Maryland Transit Authority to procure only zero-emission buses. Vermont H0094 specifies that Type I and Type II school buses ordered in 2022 must be plug-in, along with any vehicles used for fixed route services. Maryland’s omnibus climate bill SB414* sets 2030 as the state’s target date for an entirely zero-emission state fleet. Similarly, Hawaii SB920* and HB552** set target dates of 2030 and 2035, respectively, for light duty vehicles. New York A02412 sets 2032 as the date after which passenger vehicles purchased by any agency or public authority of the state must be battery electric or plug-in hybrid, and S02838* requires that at least 50% of state agency vehicles are zero emission by 2030. Bills like Massachusetts H3255 and S2139 set 2035 as the date by which fleets must be entirely electric (with interim targets), while Rhode Island H5537 and S0042 propose beginning at 15% zero emission vehicle purchases or leases in Fiscal Year 2022, ramping up to reach 50% by 2030. S2130 specifically addresses electrification of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s passenger bus fleet, requiring the operation of only zero emission vehicles by 2040.

Other state legislators are taking a slightly different approach. Some ask or tell state agencies, cities, counties, and towns to prioritize zero emission vehicles in their upcoming purchase and lease decisions, like Arizona SB1152 and HB2664. Minnesota HF1668 and SF1684 establish a preference hierarchy for vehicle procurement, and Hawaii HB424** and SB303 require vehicle rentals for official government business to be electric or hybrid when possible. New Jersey S1010* allows county and municipal bonds to help acquire electric and alternative fuel vehicles, and Connecticut SB00725 looks to create incentives for the use of electric vehicles in municipal fleets. California AB1110 also considers ways to reduce barriers to zero-emission fleet adoption, including bulk purchasing options and other financing options.

It is worth noting that, while not yet a full-blown trend, legislators are beginning to consider ways to cut off the purchase and registration of new private non-zero emission vehicles, following California Governor Newsom’s executive order in late 2020. These include California AB1218 and Massachusetts H3541 with 2035 cutoff dates, and Massachusetts H3329 with 2038. New York S02758 and A04302* similarly set 2035 as the date after which in-state passenger car sales must be zero emission, but also require that 100% of medium- and heavy-duty vehicles must also be zero-emission by 2045. Maryland HB592*, as amended, also chooses 2035 for all light-duty vehicles, but 2030 for all passenger cars in the state fleet. Washington State’s legislation is the most ambitious, with HB1204 requiring all new public and private light duty vehicles to be electric by 2030. HB1287** also chooses 2030, but conditions it upon achieving at least 75% participation in a statewide road usage charge (or equivalent).

3. States Debate the Future of Natural Gas

With coal in retreat nationwide, the push to decarbonize has begun to move beyond power plants and all the way into new homes and buildings, now with a focus on natural gas. This is not without opposition. Dozens of municipalities in California, Massachusetts, Washington, and Colorado are looking to restrict natural gas hookups in new or significantly renovated construction, and some state legislators have begun to push back, even taking preemptive action.

Arizona, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Louisiana passed legislation in 2020 to preempt localities from passing ordinances or raising fees to prohibit or otherwise restrict the use of any utility service based on its source of energy, and other states are now using the same playbook. So far in 2021, similar language has popped up in at least 18 states. Bills already signed by governors include Indiana HB1191**, Kentucky HB207**, Arkansas SB137**, Utah HB17**, Wyoming SF0152**, Mississippi HB632**, Iowa HF555**, Alabama HB446**, Georgia HB150**, Texas HB17**, and West Virginia HB2842**. By the time you read this post, Florida HB919**, Missouri HB734** and Kansas SB24** may have also received a final signature. North Carolina HB220, and Ohio HB201* have each made it through their chambers of origin, while Ohio SB127 and Pennsylvania SB275 await action.

Among these “ban on bans” bills, only Colorado’s HB1034 has been postponed indefinitely, facing strong headwinds from a legislature more inclined to take proactive steps toward building electrification (see SB246* and HB1286). Other states also see proactive legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the built environment, including California SB31, which would implement programs and planning related to building decarbonization, and Minnesota HF751, which allows utilities to file plans to promote energy end uses powered by electricity in residential and commercial buildings.

An ambitious bill filed in Washington, HB1084, sets up a gas utility Integrated Resource Planning process and a Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission investigation. “Transition Implementation Plans” must consider multiple strategies to achieve gas utility greenhouse gas emissions reductions, including energy efficiency and thermal load reductions, decommissioning of portions of the gas distribution system, and reduction of the carbon content of delivered gas. AB380 is a similarly significant bill filed in Nevada to study and plan for the future of the natural gas system through a gas utility Integrated Resource Plan and an investigatory docket, and Massachusetts H3298 requires that the Department of Public Utilities actively encourage a transition away from the use of gas or other emitting fuels.

4. Legislating Resilience Against Climate and Weather Threats

No surprise here, grid resilience and emergency management takes a Top 10 spot in 2021. What might be surprising is the range of approaches that legislators are taking to prepare for the expected unexpected. Also notable, some bills are going further to consider the interdependence of vulnerable infrastructure and systems, including water, gas, agriculture.

Texas tops our list of states thinking about resilience, with over 60 bills filed this session to respond to the devastating February power outages. These include the omnibus weather emergency prepare, prevent, and respond bill SB3*, HB11* to require utility weatherization, HB2000* and HJR2* to provide funding for reliability projects through a State Utilities Reliability Fund, and SJR62 and SB1750* to create a Reliability Fund and coordinate winter preparedness plans between natural gas and electricity infrastructure. HB1607* considers expanding transmission to enhance reliability, while HB4120 promotes electric school buses as a grid resource that can provide backup power. SB415* allows transmission and distribution utilities (TDUs) to contract for battery energy storage to provide reliability and resilience, and HB2483* allows TDUs to lease distributed energy resources for emergency power.

California is next, evaluating bills such as SB45 to authorize bonds to fund wildfire prevention, drought preparation, flood protection, and safe drinking water, SB99* to offer technical assistance and grants to help local governments develop clean energy resilience plans (think: microgrids, mobile energy storage, distributed energy resources and electric vehicles), and AB9 to establish a Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program to create fire-adapted communities.

Colorado HB1208* creates a Natural Disaster Mitigation Enterprise to collect fees on insurance companies for mitigation measures, SB054** appropriates millions of dollars for forest restoration and wildfire risk mitigation, wildfire preparedness, and watershed restoration programs, and HB1242* looks to prepare the agricultural industry for climate, drought, and other hazardous events or disturbances. Oregon SB288 looks to expand interagency coordination to prepare and plan for safety and resilience after natural and manmade disasters, while Washington HB1147 creates a statewide disaster resiliency program to work in conjunction with a climate resiliency program. Also concerned about wildfires, Washington HB1168** creates an account for forest restoration and community resilience against vulnerabilities.

On the opposite coast and vulnerable in different ways, Florida considers some of the same approaches to resiliency. S1360 and H1105 create an energy and disaster resilience pilot program that supports the use of energy storage and distributed energy resources during natural disasters and declared states of emergency. SB2514** and H7019 each create a Resilient Florida Trust Fund for the Resilient Florida Grant Program and the creation of a Statewide Flooding and Sea-Level Rise Resilience Plan.

Just north of Florida, North Carolina H500 establishes an Office of Recovery and Resiliency for multi-year projects and S509 creates the Energy Resilient Communities Fund to help local governments with clean energy projects like energy efficiency and renewable generation. Bills in Maryland modify the Clean Energy Loan Program to include grid resilience projects (SB319* and SB54) and appoint a Chief Resilience Officer to coordinate state and local resilience and hazard mitigation efforts (SB62 and HB542). New York A01008* directs utilities to submit storm hardening and system resiliency plans, and A05386 considers harnessing soil health to reduce negative environmental impacts and sequester carbon. It also establishes a Climate Resilient Farming Program to reduce the effects of farming on climate change, and visa versa. Massachusetts S2156 asks utilities to assess the resiliency of their transmission lines, and H2159 requires municipal master plans to include renewable energy elements and identify vulnerable populations and infrastructure.

5. What Should Electric Vehicle Drivers Pay?

State legislatures across the country are having hard conversations about the future of their roads and highways, and how to pay for their upkeep. In most states, the gasoline taxes that were supposed to pay for roadway maintenance have not changed in decades, not even keeping pace with inflation. Rising fuel efficiency has meant that revenue from gas-powered travel has dropped. Into that conundrum have come electric vehicles (EVs), which don’t pay the gas tax because they don’t use gasoline at all. Though market share of EVs in most states is still hovering between 1% to 2% – not nearly enough to impose “wear and tear” on the road or make a dent in state highway funds – plug-in vehicles have gotten swept up into transportation infrastructure funding debates. These cars are increasingly being required to pay more than their fair share, thereby discouraging their adoption.

At least 14 states have seen legislation proposing flat annual or biannual registration fees, or increases to existing plug-in vehicle registration fees, but a handful of others are getting more creative. Most, but not all, of the following bills impose special costs on vehicles that operate exclusively on electricity or use a hybrid of technologies. Montana HB188**, Louisiana HB615 and HB582, Texas SB1728* and HB427, Utah HB0209, Minnesota SF1086, Pennsylvania HB1358, and North Dakota HB1464* propose fees at or above $200 for battery electric vehicles – considerably more than typical drivers of gas-powered vehicles. Florida’s S1276 does as well, but the fee would only kick in once EVs make up 5% of the total number of registered vehicles in the state. Texas HB2221 and HB3797, Illinois HB2833*, Colorado HB1205, and Arizona SB1108* and HB2437 propose fees at or around $100, some of which (like the Colorado bill) are intended to be layered on top of existing EV fees. Colorado’s SB260* takes a unique approach, proposing a gradual, non-linear phase-in schedule over 10 years. Florida S0140, Kentucky HB508, and Texas HB2986 set fees that differ depending on vehicle weight.

Idaho H0361 proposes to increase the existing EV fee to $300, but offers to waive it if drivers participate in an alternative program that charges $0.025 per mile. Washington SB5444 is also proposing an opt-in (until mid-2026) $0.02 per mile fee as a substitute for a $75 annual flat fee. Vermont H0123 creates a per-mile tax (also known as a “road usage charge,” or RUC), as does Minnesota HF523.

Meanwhile, a few legislators are exploring charging EV drivers with a tax on the electricity that they use. Oklahoma HB2234** and Nevada SB384 propose an electric charging tax of $0.07 per kilowatt-hour, and Nevada SB191 proposes a 10% surcharge on total electricity consumption at the charging station.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, California’s SB542 proposes to repeal the state’s existing $100 fee.

6. An Offshore Wind Blowing Through Coastal Legislatures

While the rise in offshore wind legislation may be limited to coastal states, it is nevertheless a trend that continues to grow. A number of bills set specific procurement targets, like California AB525 (10,000 MW by 2040), Oregon HB3391 (3 GW by 2030) New Jersey S3667 (7 GW by 2035) and Massachusetts H3266 (4,800 MW by 2025) and New Hampshire SB151 (800 MW by 2028).

California AB413 directs the California Energy Commission to plan for 10,000 MW by 2040, and Oregon HB3375* creates a Task Force on Floating Offshore Wind Energy to ensure effective planning, ecosystem, and fisheries protection. Rhode Island H5108 directs the state to establish timetables to increase clean energy resources, including offshore wind, in pursuit of 100% renewable energy, and Maine LD336 allows an entity to petition the Public Utilities Commission for a long-term contract to facilitate research on floating offshore wind on the outer continental shelf of the Gulf of Maine. Maryland HB376** restricts municipal utilities from using offshore wind to meet more than 2.5% of their renewable portfolio standard requirements.

Bills in Virginia (SB1295**) and New York (A06400 and S04955) focus on domestic or in-state manufacturing, giving priority to offshore wind projects that benefit their state economies, while bills in Massachusetts (H3310) and the U.S. Congress (HB998) look to harness the workforce development potential of this renewable resource.

On the flip side, Maine LD1010 and LD1619 prohibit new offshore wind development, and South Carolina H3204 requires that all wind facility applications demonstrate that they will not adversely impact military operations before receiving approval. Massachusetts H953 commissions a study on the effects of offshore wind projects on fisheries, and H3373 creates a Wind Energy Relief Fund to compensate for any losses caused by offshore wind, including those related to detrimental health effects and property value.

7. Extending Final Lifelines for Coal

Across the country, coal-fired generation is on its way out, no longer cost-effective or sufficiently flexible to operate in an increasingly dynamic and market-driven energy environment. Indeed, legislation allowing for securitization to reduce the coast of coal plant retirement is on the rise (see Missouri HB734**, Indiana SB0386**, Kansas HB2072**, and Minnesota HF1189. New Mexico SB156 tweaks previous securitization legislation).

Still, lawmakers in a number of states are attempting to buck the trend. Many of their bills contain preambles that declare it a matter of state policy to support the continued operation of coal-fired power plants for reasons related to reliability, grid stability, affordability, national security, state and local economies, and jobs. Of the following bills, all have crossed their respective legislative finish lines except for Montana SB176, HB695*, and SB379*.

Wyoming has done the most to try to save their coal-fired power plants, enacting bills like SF136** to allow the Public Service Commission to consider availability and reliability of service when determining electric rates, and economic and employment externalities when reviewing plans and applications for the construction or retirement of major energy facilities. Also signed into law, HB166** establishes a presumption against the retirement of existing generation and prohibits rate recovery or earnings on facilities built to replace generation from a retired coal or natural gas facility for which the presumption against retirement was not rebutted. Most aggressively, Wyoming’s HB207** allows the Governor and Attorney General to commence lawsuits to challenge other states’ laws that restrict the use or import of Wyoming coal by causing the early retirement of coal units. The bill carries an appropriation of $1.2 million to pursue this litigation, with the option to request more if needed. It is worth noting here that most observers do not expect these lawsuits to be successful, some even going so far as to call this bill “a waste of money.”

HB1665** in Arkansas tells its Public Service Commission that it is in the public interest to promote, encourage, and extend the use of existing generation units throughout the rest of their useful lives, and West Virginia uses SB542** to stipulate that coal facilities should continue to provide baseload generation. SB542 also requires that utility-owned coal plants maintain a 30 day aggregate coal supply, and directs the Public Service Commission to consider all economic impacts associated with the plants when making relevant decisions, to reverse the trend toward plant closures, and to maintain coal employment levels for West Virginians.

North Dakota’s HB1452** includes coal, oil, and natural gas in the definition of “low-emission technologies,” and passes Concurrent Resolution 4012** to declare that non-dispatchable energy resources present major challenges to bulk power system reliability and resilience, to instruct North Dakota to coordinate with its Regional Transmission Organizations on policies to discourage premature retirement of thermal generation, and to support the development of carbon capture utilization and storage. In the same vein, South Dakota’s Concurrent Resolution 6010** encourages the “responsible” development of domestic fossil fuels, and Montana Joint Resolution 10** urges funding of carbon capture research, development, and commercialization, while also explicitly resisting “interferences” that threatens the viability of the Rosebud Mine, the Colstrip Electric Generating Station, and other coal operations across the state.

Though not all have become law, Montana legislators have also filed bills to use rate recovery provisions, coal severance tax statements in support of coal, remediation costs, rebuttable presumptions of prudence for utility coal costs, and legal action against unfair or deceptive trade practices to protect the ongoing operation of state coal plants (see SB176, HB695*, SB379*, and SB266**).

8. What Happens to Workers?

As the clean energy transition powers forward, questions remain about how to best help workers displaced from fossil fuel industries. As a result, energy workforce considerations are appearing in an increasing number of bills across the country.

As with environmental justice, these bills sometimes address workforce issues exclusively, and other times have a different primary focus but include workforce provisions. Workforce-focused bills include the Illinois Clean Energy Jobs Act (HB0804 and SB1718) and Illinois HB2647. Texas HB3894 establishes the Texas Workforce Commission to create a Just Transition Skills Development Workforce Program, and HB3878 and SB955 call for the Governor to establish a Committee on Economic Development and Workforce Retraining for the clean energy transition. In Colorado, HB1149* calls for the development of an industry driven energy sector career pathways curriculum, and HB1290* appropriates $8 million to the Just Transition Fund and $7 million to a coal transition worker assistance program. Massachusetts H602 requires the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education to establish a clean energy program to fund technical and vocational high schools to ensure workforce training and job placement in renewable energy industries.

Maine and Connecticut take a slightly different approach: LB1231 requires that renewable energy projects receiving above $50,000 in state assistance offer workforce development and apprenticeship programs, and SB00999* requires that renewable energy projects with a total cost of $2.5 million or more also establish workforce development programs. Maryland HB1007** also requires that at least 10% of employees working on the installation of geothermal systems be enrolled in apprenticeship programs approved by the state or federal government. Massachusetts H3302 allocates at least 1% of offshore wind project costs to fund wind power research and related workforce development. As noted below, many have pegged the offshore wind industry as an engine of job creation, with bills like HB998 before the U.S. Congress, Virginia SB1295**, and New York A06400 and S04955.

Of the bills within which workforce is one piece among others, Rhode Island S0078** requires that the state’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction plan identify support for workers to provide an equitable transition. Florida’s omnibus renewable energy bill, H0283, creates a Renewable Energy Workforce Development Advisory Committee to identify workers in the energy sector, the employment potential of the energy efficiency and renewable energy industries, and what skills and training workers entering those fields need. Virginia’s Green New Deal Act, HB1937, establishes the Transitioning Workers Program to provide jobs, training, relocation support, income and benefits support, and early retirement benefits, while also developing trade programs for high schools and community colleges. West Virginia SB542**, which is intended to support ongoing coal operations, also calls for the state to provide education, training, and retraining opportunities for displaced coal miners.

Finally, natural gas workers are emerging as a target audience for workforce development, as a handful of states are beginning to think about the future of natural gas in the built environment and transportation electrification. These bills include Nevada AB380 to set up an investigatory docket that would consider, among other things, workforce impacts of building electrification and plans to transition workers into similarly compensated jobs and Massachusetts S2148 to provide for a gas transition trust fund that would help retrain gas pipeline workers to comparable jobs on “non-emitting renewable thermal energy infrastructure.” Meanwhile, New Jersey A5569 authorizes vocational school districts to establish an electric vehicle (EV) certification program to train students for careers in EV-related fields.

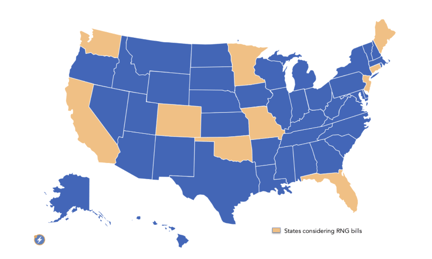

9. The Rise of Renewable Natural Gas

As states grapple with questions about the long-term viability of greenhouse gas-emitting natural gas, renewable natural gas (RNG) has piqued some legislators’ interest as a potential pathway for use of existing pipeline infrastructure in a zero-carbon future. Others see RNG as an excuse for natural gas utilities to stay in business and a distraction from cost-effective electric alternatives. Still, legislative curiosity remains.

As states grapple with questions about the long-term viability of greenhouse gas-emitting natural gas, renewable natural gas (RNG) has piqued some legislators’ interest as a potential pathway for use of existing pipeline infrastructure in a zero-carbon future. Others see RNG as an excuse for natural gas utilities to stay in business and a distraction from cost-effective electric alternatives. Still, legislative curiosity remains.

Some bills, like Missouri HB892 and HB734**, Florida H0539 and Florida S0896** take steps to require their Public Service Commissions to allow for RNG programs and cost recovery for utilities. Under HB1815**, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission must issue a report and recommendations to the legislature regarding the ability and appropriateness of natural gas utilities getting into the RNG business. It also calls for educational materials to inform customers of the benefits of RNG. Minnesota SF421* and HF239 allow natural gas utilities to file innovative resource programs that include RNG, and Connecticut HB06409 allows the state to solicit biogas to inject into the natural gas distribution system.

Other pieces of legislation create explicit RNG targets. Maine’s LD989 allows gas utilities to use RNG for up to 2% of supply beginning in 2022, increasing 2% annually thereafter. New Jersey’s S3526 and H5655 set targets of 5% beginning in 2022, increasing to 30% by 2045. SB161 in Colorado set a 5% by 2025 target, increasing to 15% by 2035, while two bills in Illinois – HB3115 and SB0530 – contemplate a 2% RNG blend by 2030 and a 3% blend by 2035.

At a higher level, Washington HB1084 allows the use of renewable natural gas, green hydrogen, and other low-carbon fuels in its gas utility Integrated Resource Planning Process, and Colorado SB264 requires gas distribution utilities to file clean heat plans before the Public Utilities Commission, which may use RNG to meet a target of 20% greenhouse gas emissions reduction below 2015 levels by 2030.

And what might be the next frontier in “renewable fossil fuels?” Perhaps renewable propane. Appearing in only California and Washington, AB1559 looks to create financial incentives for renewable propane, derived from sources like renewable feedstock, hydrogen, and renewable dimethyl, and HB1091** simply includes it in the definition of “biogas.”

10. Electrifying Parking Spaces

Mass deployment of charging infrastructure is seen as at least half the battle to reach mass adoption of electric vehicles (EVs). Yet, new construction is not often coming pre-wired for the eventual installation of Level 2 Chargers. Rarer still is the charging station itself, even though retrofitting parking spaces later to host charging infrastructure can be expensive and disruptive. Legislators across the country are looking to either mandate enough electrical capacity to host EVs through legislation or direct state agencies to add “make ready” requirements for future charging capacity into building codes.

To begin, New York S00370 and A00346 require a certain percentage of parking spaces in large garages and lots to offer charging, while A03179 does the same for all new construction or substantial renovation, with certain percentages of spaces that need to be “EV-ready” and another percentage that need to have an installed station. A03435 uses a ratio of spots dedicated to install electric vehicle supply equipment at all new residential and commercial construction with off-street parking. S00023* and AB4386 require that all parking facilities built with state capital funds support EVs. Rhode Island S0173 and H6253 also require certain percentages of spots to have EV charging in new or expanded lots, as do Hawaii SB756*, HB803*, HB802 and SB763, all by specific dates. Virginia’s HB2001** requires sufficient charging infrastructure for EV passenger fleets at new state and local governmental buildings.

Using the building codes approach, North Carolina (H342), California (AB113 and AB965), Pennsylvania (HB481), Washington (HB1287**), Oregon (HB2180**), Hawaii (SB773 and HB1140) Massachusetts (S2192, H3347, and S2151) direct the relevant state agencies to include building standards for EV make-ready and charging station installations. Some bills target the single family residential, multifamily residential, or the commercial building code. Some tackle all three. A slight variation – Arizona SB1102 – instructs municipalities to withhold building permits for single-family residential structures if that structure is not equipped for EV charger installation.

While this legislation passed D.C.’s City Council last year, DC B23-0193** was signed by the mayor on January 13. It requires new construction and substantial renovations of commercial and multi-unit buildings with off-street parking to have EV make-ready infrastructure at a minimum of 20% of parking spaces.

For EV charging while on an outdoor adventure, Oregon HB2290** and North Carolina H641 look to provide public charging stations at state parks. And last, but no less important, California AB970 looks to expedite the permitting application process for installations.

Honorable Mention: Siting and Permitting

While there is perhaps no unified goal among the bills that address electric generation siting and permitting, finding locations and getting approval for advanced energy projects is getting more challenging. Aware of the problem, state legislatures are considering a number of bills that take on a variety of flavors, some in favor of advanced energy resources, some against. Some incent or disincent certain land use (Maine LD820**, Rhode Island H6169, Massachusetts S2174, and New York S01829*), others add new siting standards and considerations (Indiana HB1381*, Alabama SB80**, South Carolina H3204, Virginia HB2201** and SB1207**, Texas SB1003*, Missouri HB970, Kansas SB279, and Ohio SB52 and HB118) or alter siting and permit processes (Ohio HB2063**, Illinois SB1602, Wisconsin AB27**, Utah HB0436 and Massachusetts H1264). At least 11 states are considering siting and permitting as they related to environmental justice (Massachusetts S2186 and S2135, New York S01031*, Rhode Island S0105, and Virginia HB2221* and HB2074*). New York S05939 and Oregon HB2021 prohibit the issuance of permits to new fossil fuel generation, and Maine LD802 requires large solar developments to have approved decommissioning plans before development.

Claire Alford and Robert Haggart contributed to this blog post. Cayli Baker created the data visualizations for this post.

Keep up to date on all legislative and regulatory action with AEE's PowerSuite. Click below to start a free trial: